![JGH[18] | Image © Matharoo Associates](https://hawmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH18.jpg)

Architectural Group: Matharoo Associates

Principal Architects: Gurjit Singh Matharoo

Clients Name: K.P Sangvi charitable trust, Shri pavapuri tirth dham jeev maitri dham

Project Team: Ramesh Patel (Architect), Janmay Mehta (Trainee)

Project Location: Pavapuri, Rajasthan, India

Project Year: 2007-2009

Project Area: 3100 sq. mt

Project Type: Religious

Structural Consultant: Matharoo associates – R.S Matharoo, Ritesh Chauhan

Mechanical Consultants: Jhaveri Associates

Interior Design: Matharoo Associates

Landscape Architects: Vagish Naganur

Contractor: Riva Construction, Stone art, Ram-Laxaman Mistry – Surat

Image Copyright/Courtesy: Matharoo Associates

News Source: From the office of Matharoo Associates

Originating in Bihar between the 9th and 6th century B.C almost at the same place and time as Buddhism, Jainism is a religion with approximately 4.2 million followers in India. Devout practitioners of this exacting religion are expected to denounce worldly life and bonds. Customs such as living in the wilderness devoid of all encumbrances – including clothes, abstaining from any physical contact whatsoever, fasting for more than 100 days, walking barefoot for distances exceeding 1000 miles and plucking each strand of hair of their head to remain bald are the norm.

Extreme non violence, absolute renouncement, strict solitude, and severe austerity form its core beliefs. Profound concepts of space and time and the accurate definition of units such as 1 Avali – the time required to blink, have featured in Jain scriptures as far back as its inception, they are even credited with identifying the idea of the infinite.

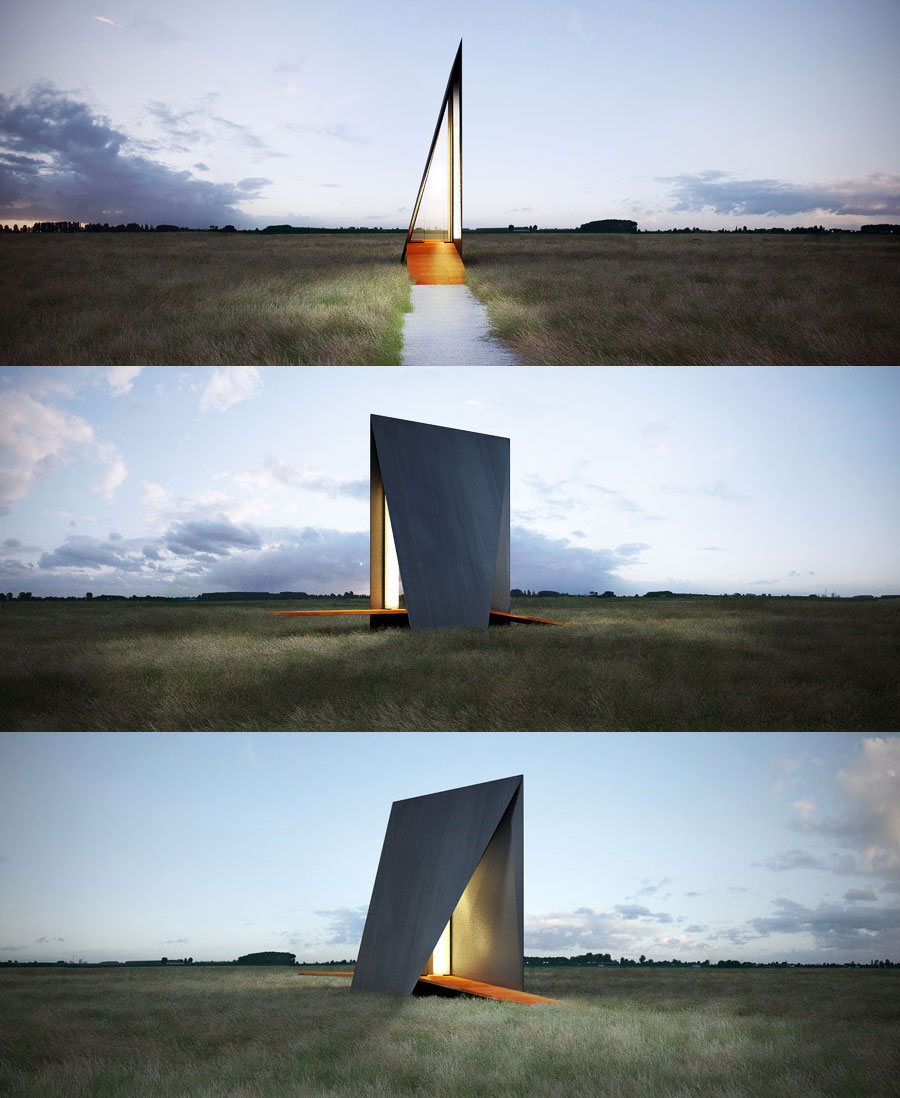

The design became an exercise in expressing these intangibles through the paradoxical creation of a void. A set of floating voids open to the rising and setting sun defined by stone blinkers became the only intervention.

![JGH[4] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[4] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH4.jpg)

These seven stark service blocks, each of a 1:4:8 proportion and the 4:4:2 entrance mass come together volumetrically to form a perfect cube when reflected in the water of the adjacent lake, which is meant to be diverted up to the building line in the next phase of construction.

Even the amphitheatre complies with this stringent geometry with a diameter of four times the basic 2.4m unit. The final effect was conceived to be like a chant, simple and repetitive, its power being in the resonance with the self inside and the extension of the self outside.

A typical Jain temple consists of linearly arranged sequential spaces beginning at the ornate entrance , leading up to a Mantapa or hall and terminating in the sanctum or garbha griha, which is topped by a tower known as the Shikhara, the entire complex is then flanked on either side by the shrines of the Tirthankaras, the founders of Jainism. This arrangement is reinterpreted in the plan of the Dharamsala with the strong linear axis maintained and translated into a defining walkway, which runs along the entire length of the building. A block is created to define the entrance at one end and the Mantapa transformed into an amphitheatre defines the other. The image of the Shikara is retained in the proposal for a bird tower and the shrines flipped along the central axis and stacked onto one side create the rooms and complete the complex.

The 24 rooms reflecting the 24 Tirthankaras, are spread over a series of modules that are fully self sufficient, each having its own services and circulation.

The modules are tied together by an elevated walkway bathed in light from above through the translucent roof that arcs over it. Evolving from an originally envisioned concrete roof, this accommodates the headroom required for the holy water held high on the shoulders of the passing Jain monks below.

[quote style=”1″]Locally available materials such as Nimbada stone laid in a masonry that is prevalent in the surrounding areas , polished Kota stone floors from quarries nearby and floor plates cast in everyday concrete make up the restrained material palette.[/quote]

In keeping with the essential tenants of Jainism, of non violence and solitude, a 100 mm wide separation is retained between all the elements of the composition rendering them pure. At the only instance where the stone blocks had to meet the ground they will eventually reflect in the lake and become suspended elements in the landscape.

Isn’t this 2500 year old Jain philosophy of never infringing on the earth evocatively similar to those aspired to by the proponents of the ecological movement today?

![JGH[18] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[18] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH18.jpg)

![JGH[2] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[2] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH21.jpg)

![JGH[7] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[7] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH7.jpg)

![JGH[6] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[6] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH6.jpg)

![JGH[13] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[13] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH13.jpg)

![JGH[14] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[14] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH14.jpg)

![JGH[12] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[12] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH12.jpg)

![JGH[5] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[5] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH5.jpg)

![JGH[15] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[15] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH15.jpg)

![JGH[17] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[17] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH17.jpg)

![JGH[11] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[11] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH11.jpg)

![JGH[10] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[10] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH10-150x150.jpg)

![JGH[3] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[3] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH3-150x150.jpg)

![JGH[16] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[16] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH16-150x150.jpg)

![JGH[1] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[1] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH1-150x150.jpg)

![JGH[8] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[8] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JGH8-150x150.jpg)

![JGH[19] | Image © Matharoo Associates JGH[19] | Image © Matharoo Associates](http://www.howarchitectworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/pavapuri-drawings-150x150.jpg)